Over at the National Catholic Register, Brendan Towell has offered a wonderful analysis of Robert F. Prevost’s doctoral dissertation for the Angelicum. Though the work is not yet available publicly, Towell’s piece—together with an interview with Fr. Thomas Joseph White, OP, now rector of the Angelicum, and a NY Times piece with some additional quotations—gives us a helpful glimpse into it.

What immediately struck me upon reading Towell’s summary is that a veritable feast of both/ands appear to be in play. (Indeed, the dissertation itself—Prevost writing about the Augustinian prior at the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas—is itself a wonderful convergence of the Church’s two greatest thinkers.)

Consider the following extracts from Towell. I’ve bolded various both/ands, many of which will be recognizable to those who have read The Way:

Father Prevost lays out a theology of authority that is as ancient as the Gospel and as urgently needed as ever.

For Father Prevost, this is not a contradiction but a convergence: The spiritual charism of Augustine and the institutional authority of the Church together define what it means to lead.

Leo XIV’s dissertation presents a vision of the Church not as a hierarchy of command, but as a communion of communities, bound together by authority that is at once legal and pastoral, spiritual and institutional.

For him, the law is not a distraction from the spiritual life — it is one of the ways that life takes concrete form. “Religious life, just as the Church as a whole, is a reality made up of visible concrete dimensions and spiritual, charismatic elements as well. Frequently, it is in and through the visible dimension that the charismatic is actualized.” Law, in this view, does not limit grace; it enables it to be lived in community and in concrete reality.

Father Prevost’s dissertation suggests he sees no contradiction between synodality and structure. Discernment, he implies, requires form. Dialogue requires rules. The superior’s role is not to suspend the law in the name of mercy, but to interpret and apply it with justice and love. As he writes . . . .“The superior and the community which he serves must work together in order to arrive at decisions which reflect a real cooperation with what the plan of the divine will would be in the given situation.”

“Freedom and law are not terms which contrast with one another,” he writes. “They are values which must be integrated with each other.”

Father Prevost insists that the Gospel does not abolish authority, but institutes it.

This framework reflects a trust in local initiative (what the Church calls subsidiarity), tempered by the Pope’s responsibility to ensure unity and care for the whole Church — a balance long held as essential to ecclesial governance.

If this emphasis on law and governance seems abstract, Father Prevost grounds it firmly in the notion of relationship.

Time and again, he returns to the conviction that leadership must be grounded in love, expressed through listening, and oriented toward unity.

He calls it an “ecclesial ministry,” recognizing that even the smallest act of local leadership participates in the Church’s universal mission.

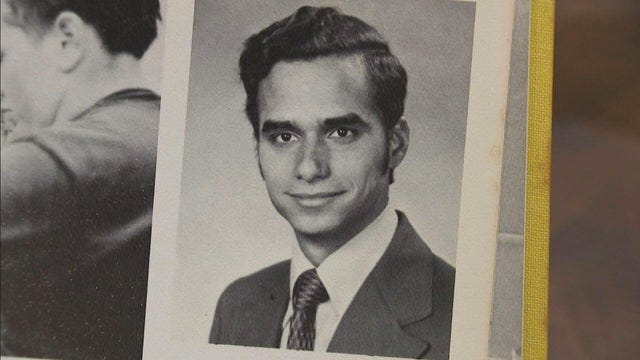

I met Father Prevost in 2010. . . . I was struck by the same combination of simplicity and interior conviction that now animates his papal vision.

His theological imagination links the local and the universal, showing that the Church’s health depends on grassroots vitality and on the unifying role of the Petrine office.

This version of synodality is likely to resemble ordered collaboration, not open-ended experimentation.

The inclusion of patristic and medieval sources . . . points to a scholar who interprets the Church’s present through the wisdom of her past.

His dissertation draws on a wide range of canonical thinkers — some deeply traditional, others shaped by the aggiornamento of Vatican II — signaling a legal mind both rooted and responsive, not beholden to any single school or ideology.

The local and the global are held together not in tension, but in mutual service.

As his dissertation makes clear, the authority Pope Leo XIV now holds . . . will be exercised firmly, clearly, and with love.

Perhaps that’s precisely what the Church needs now: not a revolution, but a return — to clarity, to charity, and to the wisdom of a simple friar who knows how to lead by serving.

Charism and institution, order and openness, truth and love, tradition and the present, the local and the universal, grace and law—music to my both/and ears!

Of course, the degree to which these various convergences of the heavenly and earthly really do permeate the dissertation, and are not just in Towell’s interpretation of it, is unclear; even more unclear is the degree to which these both/ands will come into play in Pope Leo’s pontificate, and where his particular emphases will lie to meet the challenges of the moment. Pope Francis, after all, was a man profound shaped by the principle of bipolarity, and Towell suggests here a strong contrast (though not a break) between the two men’s approaches to ecclesial questions.

Regardless, we find here strong evidence that the young Prevost was a man of exquisite Catholic balance—an encouraging sign of hope for the future of the Catholic both/and in the life of the Church.

I recently read that there is there is a saying among academic historians that a scholar's dissertation is always, in some form, an autobiography. That is, it usually is a mirror reflecting the life experiences and personal philosophy of the author. From what you've shared, this seems to be the case with the young Father Prevost.